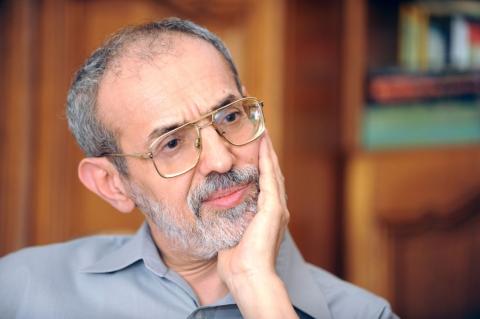

Bari Károly: Biography

Károly Bari (Bükkaranyos, 1 October 1952–)

Kossuth Prize-winning Hungarian poet, literary translator, folklore researcher, graphic designer. He has been a member of the Digital Academy of Literature since 2019.

*

Bari burst onto the Hungarian literary scene in the late 1960s, „at a Rimbaudian age and armour” as Mátyás Domokos, the literary editor who discovered and praised the poet, put it. Domokos helped in publishing the slim but all the more important volume written by the 18-year-old „astonishingly sovereign author” in 1970. The resounding success of Over the Faces of the Dead (Holtak arca fölé) is shown by the fact that it was republished the following year in a print run of 22,000 copies.

Károly Bari was born on 1 October 1952 in Bükkaranyos and was the fifth child in a Gypsy family. „My farmhouse smoking raw poverty / with its crumbling walls, its windswept roof / hung in the world, knotted in trouble to the chin” – thus he introduced himself in his poem „My Torture Started The Journey” („Kínom indított útnak”). The rapturous reception was largely due to Bari’s origins from the depths of society, a fact that, in the receptive reader, was also accompanied by a kind of „mental remorse” – to quote Domokos again. At that time, Bari spoke only in verse and only metaphorically about the upheavals of his childhood, recounting how his „black reed” mother had „taken on a lot of suffering” so that he could go to secondary school. He graduated from high school in 1972, albeit with some delay – he was forced to interrupt his studies and change high schools, and although he was immediately accepted at the University of Theater and Film Arts, that same year proved to be a watershed in his life. On 15 March, in Budapest, he was one of the few hundred young people who wanted to worship the statue of Sándor Petőfi without permission on what was then an unofficial national holiday. The demonstrators were brutally dispersed by the baton-wielding police. „Freedom: an iron-clad promise, / you wither before our eyes […] and they dare to say […] that we are free” – the poem burst from the poet, he not only read it out loud, but also told the story that inspired it at the literary events which took place in the following weeks and months.

The denunciation was followed by an interview and then a threat from the communist party: similar actions would no longer be considered a „literary matter”. And after Bari sent his poem „The Silk of Foreign Flags Strikes My Eyes” („Idegen zászlók selyme csap szemembe”) to the magazine Forrás, events escalated. The historical-allegorical title, „János Vajda’s Prayer of a Soldier in The Confessional Before the Immortal Soul of Sándor Petőfi” („Vajda János közkatona imája a gyóntatószékben Petőfi Sándor halhatatlan lelke előtt”) and the lines of the poem, which unmistakably referred to the Soviet occupation, were not tolerated by the authorities, who engaged in sophisticated retaliation. The poet, unfit for military service in peacetime, was drafted, and when, to avoid humiliation, he attempted suicide, he was sentenced to prison by a military tribunal for attempting to evade service.

After his release, the cultural policy continued to operate in the same two-faced way, as did Bari’s stubborn poet-human attitude. He expressed his conviction that „Truths are not to be kept in drawers” with another poem, „Exile” („Száműzetés”), and tried to send a message to his „singsong” brothers and sisters, as well as to his „love”, „this country of executioners”. „If they say I am broken, do not believe it.”

The seventies and eighties were a time of ostracism, of informing, and of „push and pull”. Bari may have been a student of Hungarian literature and cultural management at the University of Debrecen between 1975 and 1977, but when a lecture he had organised was banned, he wrote a letter of protest to the rector, calling him unfit for his position. Without a degree – as a freelancer, so to speak, carrying the burden of permanent insecurity – he threw himself into the folklore research he had begun not long before, travelling the Gypsy settlements of Hungary and Transylvania with a borrowed tape recorder, collecting and translating folk songs and folk tales.

In the absence of support, he took part in readings abroad for a respectable fee in order to finance his travels and the adaptations of the folk songs which he published from the second half of the 1980s onwards – mostly through self-publishing. He was a „one-man scientific institute” as described by his friend Ágnes Daróczi. This „modus operandi” remained largely the same after the regime change in 1989. It is not only the processing of more than two thousand hours of recordings collected over almost four decades, but the preservation of the audio material and the publication of the recordings which rest unchanged and decisively on Bari’s fragile shoulders. Ha has been struggling with his illness for many years, not resting until 2010, when he summarised his four decades of ethnographic fieldwork in the Amaro Drom magazine’s supplement On Gypsies (A cigányokról), in which he also explained why he still considers the term „Gypsy” to be more appropriate and accurate than the politically correct term „Roma”. Then in 2013, he published a grandiose, three-volume sourcebook entitled Old Gypsy Dictionaries and Folklore Texts (Régi cigány szótárak és folklór szövegek), the editorial introduction of which is more than a hundred pages of stirring self-confession and a sad historical vision of what remains unresolved in decades of prejudice and discrimination.

„I’ve also reached the point where I’m only interested in my work: only in writing! […] I can’t stand the opportunists, the moral whores – or even the dilettantes […] ’'m lonely.” He confessed this back in 1979 to his fellow poet András Mezei, who asked him in the column of the literary and public weekly Élet és Irodalom how Károly Bari saw himself. A decade later, in 1990, the same two had a conversation published in the daily newspaper Magyar Nemzet, and Bari, in an unusually revealing interview entitled „The fate that can be fined for a poem” („Ami sors egy versért kiróható”), said that loneliness was a „natural poetic state”.

In the first twenty years of his poetic existence, up to the fall of communism, Bari published only three slim volumes and one thicker book of poems enriched with picture poems and drawings. The reason for this was not so much the very real struggle with the non-existent censorship, but rather the fact that Bari spent years writing and re-writing his works. In his afterword to the 2019 volume, The Adoption of Immobility (A mozdulatlanság örökbefogadása), which summarises his 54 creative years, he also emphatically indicates that he mostly just „corrected the previously unnoticed, unedited, editing errors and corrected a few words or a few lines”. But let us add: sometimes he also corrected back. For example, he smuggled the 1972 incriminated „Freedom” into his 1983 volume The Book of Silence (A némaság könyve) under the (pseudo)title of „Yannis Ritsos” („Jannisz Ritszosz”), moving the „setting” of the „subject” to Greece.

Because of the themes and moods of his poetry and his work as a folklorist, Károly Bari is often called a „Gypsy poet”, a claim he self-consciously rejects every time. „For me, Gypsy origin means a double bond, I see my duty to my own people in ethnographic work”; „origin is not an aesthetic category”; „I am a Hungarian poet”, he always firmly states. „I have never been included in any Gypsy anthology of my own volition” – he once said. And if someone did so without his permission, he protested immediately and vehemently.

His book publications were literary events before and after the regime change, but he rarely published and preferred to remain silent for long periods. He justified this by saying that „it is not possible to write poetry all the time, because routine solutions usurp the work, they drain the style”, and in such cases it is almost a poetic duty to pause writing poetry. As a result of these pauses and silences, which have enormous poetic rewards, Bari has often been forgotten, or has been left out of the canon, or has not even became part of it. The dates of his prestigious awards and prizes reinforce the view that he has been rediscovered volume after volume.

After a 33-year hiatus, the 1985 volume The Magician Goes for a Walk (A varázsló sétálni indul) was followed by Silence (Csönd), which brings together the output of a decade and a half. It contains only twelve densely woven poems – in Bari's words, „sketches of passing in the glow”. From Silence, lines of reflection on fate scream out, such as our life is really „a journey from non-being / through non-being / into non-being”.

A collection of his life’s work, The Adoption of Immobility (A mozdulatlanság örökbefogadása), summarised at the age of 67, is a „mixed” book. It contains all his found poems, his verse and typescripts, his paintings and ink drawings, as well as his very rare prose works. The self-designed volume – which, with its typography and black and red colour scheme, pays homage to Attila József’s last book of poems, It Hurts Very Much (Nagyon fáj) – ends with a brief, but all the more self-conscious epilogue. The poetic oeuvre – including the picture and letter poems – is less than 150. „Supposedly, in terms of number, it’s extremely small, but whatever the number, I created them.”

The biography was written by Gábor Murányi, translated by Benedek Totth and Austin Wagner.