Erdélyi József: Biography

József Erdélyi (Újbátorpuszta, 30 December 1896 – Budapest, 4 October 1978)

Poet, writer. Elected a posthumous member of the Digital Literature Academy on 4 June 2020.

*

József Erdélyi was born on 29 or 30 December 1896 in Újbátorpuszta, near Feketebátor (now Batăr, Romania). His original surname was Argyelán, which was Hungarianised to Erdélyi in 1907, together with his father and five brothers (of whom József was the third). His mother, Erzsébet P. Szabó, was Reformed, and his father, János Argyelán, was a Greek-Catholic farm servant. In 1906 the whole family joined the Reformed denomination. The family, which used the Hungarian language at home, lived in relatively good financial circumstances, and thanks to the support of their landlord, all six boys were able to attend grammar school. József Erdélyi was educated at the Reformed elementary school in Árpád, the grammar school in Nagyszalonta, the state teacher training school in Deva, and finally the grammar school in Mezőtúr. His first poems were published in 1913 in the school’s yearbook.

In May 1915 he enlisted as a soldier and was sent to the Russian front. He graduated from high school in 1916, completed officer school and returned to the front. He was discharged for mental exhaustion, but took part in the fighting again in 1917 and 1918. During the war he wrote diaries and poems. The material from his manuscript notebook was published in 2015 in a volume entitled „…az irodalmat úgyis megette a fene” (‘...literature has gone to blazes anyway’). He returned from the front as a lieutenant, but was considered a deserter. He moved to Budapest, where he worked as an armed guard, later fought in the Red Army and joined a university battalion, from which he resigned without being reported in the autumn of 1920.

In 1916, his poems were published in the Kolozsvári Szemle, after which he tried to publish his works in various forums. At the beginning of 1919, he published poems in Lajos Hatvany’s magazine, Esztendő. Eventually, his poems appeared in the comic magazine Bolond Istók, and at the end of 1919 the weekly Gondolat published his anti-Semitic poems welcoming the counter-revolution. Unable to find an apartment in Budapest, he was destitute but did not look for a job, and for the next decades he tried to live solely from his poetry. From 1921 onwards, his poems were published in an increasing number of places, in a style that reflected the growing influence of folk poetry and a move away from his eclecticism (his earlier free verse and metered poems had shown a mixture of folk romanticism, Ady and other Western writers, folk poetry and soldier’s anecdotes). He published in Nyugat and several other periodicals, but by 1922 his most important medium was the ‘Christian political daily’ Szózat. In the first half of the 1920s, he travelled the country on foot, but as a person with neither Hungarian citizenship nor a residence permit, he was repeatedly arrested and attempts were made to deport him from the country, and for a time he was imprisoned in Fogaras. He escaped back to Budapest in March 1922, and in the summer of the same year his first volume, The Violet Leaf (Ibolyalevél), was published. The volume evokes sympathy across a relatively broad spectrum: it can be read in terms of contemporary nationalism, but also in opposition to it (for example, a Nyugat critic wrote that its poems contain ‘universal human images’ and ‘ancient symbols’ that are ‘perhaps common to the poetry of all peoples’).

The attention József Erdélyi garnered with The Violet Leaf helped him to break with Szózat in 1923 and become a regular, monthly-paid writer for the literary column of The Est newspaper. Erdélyi published more than thirty poems in 1923 and more than seventy in 1924. In 1925, Athenaeum published his second volume, At the End of the World (Világ végén). In January 1925, he was granted Hungarian citizenship and married Ilona Kiss, a kindergarten teacher. In November of the same year, their daughter Honor was born. Public opinion regarded Erdélyi as an established author in the second half of the 1920s, and some of his contemporaries warned him against excessive popularity and mass production. However, it was also taken as evidence that publishing poetry collections was not a profitable business, and so the fact that his next books were published by the author did not cause any sensation

The first of these, 1927’s Mirage and Rainbow (Délibáb és szivárvány), containing only nine poems, was intended by Erdélyi as the first in a series of booklets which he planned to distribute at weekly fairs around the country, but which ultimately came to nothing. The following year he published a more substantial book entitled The Last Imperial Eagle (Az utolsó királysas). This book was the subject of a much-mentioned debate in Nyugat, with Jenő J. Tersánszky and Aladár Tóth arguing for the value of Erdélyi’s poetry, while Pál Ignotus sought to show that Erdélyi was a representative artist of the ‘anti-intellectual sentimentality of youth’ and that his popularity meant ‘the rehabilitation of banality’. In 1929 (and again in 1931 and 1933) Erdélyi was awarded the Baumgarten Prize, and in 1931 he spent three months in Paris, publishing his volumes Blackthorn Flower (Kökényvirág – 1930) and Mottled Feather (Tarka toll – 1931).

In the early 1930s Erdélyi became a writer for Népszava. One of his most quoted poems, Polo in Vérmező (Lovaspóló a Vérmezőn), was published in this newspaper. Social and political themes became more prominent in his poetry. However, in the first half of the decade his newspaper appearances gradually diminished. By 1932, his most important publication forums were literary journals, Nyugat and Napkelet. A collection of his love poems, written after he fell in love with a humanities student at the Balaton Writers’ Week in September 1932 and planned to divorce his wife, showed his intention to return to the wider public. He printed the poems, collected under the title The Sun Has Risen (Felkelt a Nap), in newspaper format and began selling them outside the National Theatre in November 1932, declaring that this was his way of displacing other publications on the market. Although Erdélyi shortly gave up selling on the street, the campaign attracted widespread attention. More than a dozen articles came out discussing the relationship between poetry and the market. His rhapsodies, in which he attempted to build larger structures than he had previously done by associatively juxtaposing smaller units of repetitive form, showed his intention to renew his poetry.

By the mid-1930s, Erdélyi was without a regular and secure publication and his art in general was attracting less and less attention. At the 1935 Book Day, he appeared in protest with a sign reading: ‘József Erdélyi, the well-known poet, personally sells his works here, and, being excluded from all tents, asks for the patronage of the public.’ In the second half of the year, with money from his brother Ferenc, he founded his own newspaper, Weapon, but only two issues were published. In the following years he wrote and published more poems. In 1936, his poems appeared in newspapers of various orientations, such as the pro-German, pro-fascist Új Magyarság, which supported his increasingly extreme revisionist, anti-Semitic, anti-Soviet, anti-war propaganda, the ethnonationalist Válasz and the social-democratic Népszava. In 1937, in an evergrowing series of lawsuits against writers, he was tried for several of his poems on charges of incitement against the landowning class. These cases aroused widespread sympathy.

In 1937, the number of Erdélyi’s published poems and publication forums continued to rise. One poem, however, attracted more attention than any of his earlier work. In early August 1937, a controversy involving more than thirty articles on The Blood of Eszter Solymosi (Solymosi Eszter vére), which was published in the Hungarist newspaper Virradat and recalled the Tiszaeszlár blood libel, erupted in the press. The catalyst for the polemic was Mihály András Rónai’s A Poet’s Death. A number of articles attacked his claims that Erdélyi, who disavowed honour and humanism, was thus revealed never to have been a poet. The debate on literary theory and socio-political issues, which was of crucial importance at the time, was varied in tone, and once again focused its attention on Erdélyi. Ten days after the publication of The Blood of Eszter Solymosi, the Bartha Society announced the publication of a collected volume of Erdélyi’s works. The book, titled White Tower (Fehér torony), was confiscated because of the inclusion of poems that had previously been objectionable to the authorities, but it was still a resounding critical success. It received detailed and appreciative reviews in prestigious newspapers. Articles reviewing his entire oeuvre, with the intention of canonising it, unanimously assigned to Erdélyi the role of a revitaliser of Hungarian literature, which had fallen into crisis after the war, and of a catalyst of the ‘new folk’. At the same time, an alternative process of canonisation was set in motion in the extreme right-wing and national socialist public, which interpreted Erdélyi’s career, culminating in the publication of The Blood of Eszter Solymosi, as a rebirth of Hungarian racial consciousness.

In 1937, he published his first collection of linguistic writings (Eb ura fakó), in which he criticises linguistics for not taking into account the alleged independent meaning of the sounds that make up words. In 1938, the Nemzeti Front, of which Erdélyi was a member for a year, published more of his poems under the title Eternal Bread (Örök kenyér), including The Blood of Eszter Solymosi, omitted from the White Tower. The following year he joined the Turul Alliance. He then signed a contract with Sándor Püski, the head of the Magyar Élet publishing house, which provided him with a steady monthly income. The publisher published several volumes of Erdélyi’s work, including a new collection entitled Memory (Emlék). Between 1939 and 1941 he founded and headed a literary and art cooperative. In 1941, he signed a contract with the Turul Association publishing house, which published his two-volume autobiography: The Third Son (A harmadik fiú) and Unarmed (Fegyvertelen), among others. Erdélyi’s books were also published by the Stádium publishing house, which published fourteen books in the first half of the 1940s, over a period of five years. He was elected a member of the Petőfi Society in early 1942, but resigned in January of the following year when the Society’s proposal to expel members of Jewish origin was rejected. During World War II, he was a constant figure in far-right publicity. His attacks on his fellow writers led ten popular writers to distance themselves from him in a joint declaration in April 1943.

In October 1944 he fled to Austria, and from October of the following year he resided in Árpád, Romania. He returned to Budapest in February 1947. He was arrested and tried for his activities during the war, and in May 1947 he was sentenced to three years in prison for war crimes and crimes against humanity. He was released in June 1948. In February 1949 he was granted a presidential pardon. He returned to the literary public in 1954. Four of his poems were published in the February 10 issue of Irodalmi Újság, with a short introduction stating that Erdélyi had ‘recognised his past aberrations’ and ‘wanted to participate with full devotion in the work of building the people’s democracy, the new Hungary’. One of the poems published here, Comeback (Visszatérés), proclaimed a refusal to distinguish ‘between peoples and peoples’ and loyalty to ‘the progressive ideal and my country’. In the same year, a collection of his poems written since 1945 was published, also under the title Comeback, succeeded the following year by a selection of his complete oeuvre under the title Rosehip Bush (Csipkebokor). From this time onwards, Erdélyi again published a large number of new poems, but his volumes, which appeared every few years, hardly elicited any critical response. For a while, the hopefulness of social change was an important theme in his works, which often gave the impression of improvisation and repeated his earlier song-like forms with little variation, but in his works from the 1960s onwards, the memory of childhood and youth became more dominant than ever. In the last decades of his life he lived on Királyhágó Street in Buda.

He died on 4 October 1978. The most complete collection of his poems was published in 1995 in a two-volume publication entitled White Tower (Fehér torony). This was supplemented by another 400 poems in the 2016 book Black Oak (Fekete tölgy).

The biography was written by Imre Zsolt Lengyel, translated by Benedek Totth and Austin Wagner.

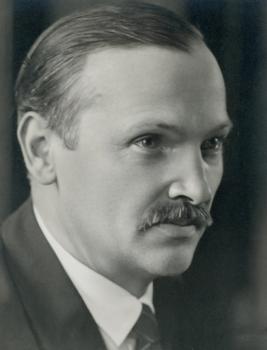

Erdélyi József, 1940-es évek (Fotó: Bérci László, forrás: Petőfi Irodalmi Múzeum)

Erdélyi József, 1940-es évek (Fotó: Bérci László, forrás: Petőfi Irodalmi Múzeum)