Bibó István: Biography

István Bibó (Budapest, August 7, 1911 – Budapest, May 10, 1979) posthumous Széchenyi Prize winner, doctor of law, politician, university professor, writer. Elected posthumous member of the Digital Literature Academy on 4 June 2020.

*

István Bibó was born in Budapest in 1911. On his father’s side, his ancestors of Reformed peasant origin worked for generations as farmers or legal officials. His father, also named István Bibó, was born in Budapest in 1877 and died in Szeged in 1935 as director of the university library. His mother came from a German-speaking Catholic farming family, so István Bibó was brought up in the Reformed religion and his sister Irén Bibó in the Catholic religion, without any tension. The family moved to Szeged in 1924. Bibó graduated from high school at the Piarist Monastery in Szeged and enrolled in the Faculty of Law at the University of Szeged in 1929. Following in his father’s footsteps, he prepared himself for an academic career, having been interested in history, sociology, politics, law and their intersections since childhood. This interest was further deepened by the shock of the Trianon Peace Treaty.

It was during his university years that his interest in politics intensified. This was mainly due to his friendship with Béla Reitzer and Ferenc Erdei. Béla Reitzer, who came from a Jewish bourgeois family and was studying to become a sociologist, passed on the most up-to-date Western European scientific literature to his friends, while Ferenc Erdei – descended from a wealthy family on one side and poor farmers on the other – introduced them to the true face of the realities of the Hungarian peasantry.

István Bibó worked in the Ministry of Justice from 1935. In 1940 he married Boriska Ravasz, daughter of the conservative Reformed bishop László Ravasz. In the summer of 1944, he issued exemption certificates to Aryan-Jewish couples and other persons in hiding, for which he was arrested by the Gestapo in October following the Arrow Cross takeover. He was released after a few days at the intercession of his ministry superiors, but from then on he had to go into hiding. He survived the siege of Budapest with his pregnant wife and their three-year-old son, and their daughter was born in a nearby hospital – without heating and with broken windows – on 2 February, while fighting was still going on in Buda. It was only in the summer of 1946 that they could finally move back to their Buda apartment.

From the end of February 1945 he became head of the administrative department of the new Hungarian government formed in Debrecen under Ferenc Erdei’s Ministry of the Interior, where his main task was the legal preparation and administration of the November 1945 elections. During 1945 he spoke out in three memoranda against the harsh and unjust expulsion of the Swabians in Hungary, and made proposals to regulate the inevitable expulsions. As this was not the responsibility of the department he headed, he was unable to achieve any real results.

In July 1946 he left the Ministry and became a professor of politics at the Faculty of Law of the University of Szeged. In addition to his university work, from 1945–48 he lectured extensively throughout the country and wrote political analysis for various newspapers. During these years, his official, public and journalistic activities were all aimed at ensuring that the democratic transformation hoped for and launched in 1945 did not falter. His first significant post-war article, The Crisis of Hungarian Democracy (A magyar demokrácia válsága), was about this very topic, as was his essay The Miseries of East European Small States (A kelet-európai kisállamok nyomorúsága), and his most important writings published in the journal Válasz until its closure in 1949: The Peace and Hungarian Democracy(Békeszerződés és demokrácia, 1946), The Warped Hungarian Self: A History of Impasse (Eltorzult magyar alkat, zsákutcás magyar történelem, 1948), and The Jewish Predicament in Post-1944 Hungary (Zsidókérdés Magyarországon 1944 után, 1948). By the spring of 1949, his publication opportunities had finally come to an end. Because he did not think, write and teach based on the tenets of Marxism, he was effectively suspended in Szeged in 1948. His post as deputy director of the East-European Institute was abolished in 1949 due to a reorganisation, as was his membership to the Academy of Sciences, which he had been awarded in 1947. His salary was halved, while his second daughter was born in September 1949, leaving him with three children to care for.

In addition to the hardships of the Rákosi era, the family was burdened by the death of the eldest daughter in March 1953 at the age of eight.

The change in the political climate after Stalin’s death did not ease the family’s grief, but it did make their life easier. The relief was soon to be associated with the name of Imre Nagy in Hungary. István Bibó, according to his surviving sketches and fragments of his essays, was following political events closely and critically even at this time, but the acceleration of events in October 1956 took even him by surprise. During the revolution of 1956 he briefly held the post of Minister of State in Imre Nagy’s third cabinet.

Between February and April 1957, István Bibó wrote a longer essay on the historical and political assessment of the revolution, which he sent abroad with the request that it be published by the press of a neutral country. The article was first published in German under the title Memorandum: Hungary, a Scandal and a Hope of the World (Emlékirat, Magyarország helyzete és a világhelyzet) in the Vienna newspaper Die Presse in September 1957.

By the time the article appeared, the author had already been a prisoner for four months. A few days before his arrest on 23 May, he received a message from his lawyer friend saying that if he were to receive the most severe sentence, he should definitely apply for clemency, so that he could use the time he had gained to intercede with foreign political forces. He responded to the message with the words of the famous 19th Century Hungarian poet János Arany: ‘From the hands of Jesus flow true mercy’s fonts’, that is: he would not ask for mercy.

On August 2, 1958, a month and a half after the execution of Imre Nagy, Bibó was also a hair’s breadth away from being sentenced to death: according to the recollection of his co-defendant, Árpád Göncz, it was clear in court that the death sentence had been commuted to life imprisonment a mere few hours before it was pronounced. It is now known that during the trial the Indian government and Nehru himself intervened on their behalf.

István Bibó’s years in prison were spent in varying circumstances. During his fourteen months of detention, he was not subjected to any physical or psychological abuse or threats. His interrogators, however, sought to ensure that the record of his activities would mostly support the charge of conspiracy against the state and that he would be convicted for his written statements.

He began serving a life sentence in Vác in 1958, where an amnesty order in April 1960 led to a hunger strike in the prison. Intellectuals who had longer sentences, notably István Bibó, Árpád Göncz and Sándor Rácz, were suspected of organising the hunger strike. In the end, they were punished with a year’s deprivation of privileges and transfer to another prison. After one year, they were transferred to Budapest, where Bibó was allowed to work in the prison’s translation office.

The situation of his family was not an easy one during his years in prison. His wife did not lose her teaching job, but her position as deputy headmistress was revoked. Instead, she was given the opportunity to teach evening classes, and her income was largely maintained.

After almost six years, István Bibó was released on 27 March following the 1963 amnesty decree, and he was faced, as the first defendant in his own trial, with the fact that the second and third defendants, Árpád Göncz and László Regéczy Nagy, who had been convicted for the same acts in the same trial, were not released on the basis of a different or stricter interpretation of the same decree. Within two weeks, he wrote a letter to the Supreme Court, exposing this absurd and unjust situation. The situation was rectified two months later and Bíbo’s other two co-defendants were released.

István Bibó continued to do his utmost to secure the release of the 400 or so freedom fighters of the 1956 Revolution, mostly students and workers whose names were unknown to the world and who received severe penalties, and were still kept in prison after the 1963 amnesty. However, Bibó succeeded in only one of their cases.

After his release in 1963, he got a job in the library of the Central Statistical Office. However, problems of subsistence meant that he had to take on side jobs – mainly translation and proofreading for a publishing house – and had very little time for his own writing. In 1967 he had a heart attack, which was followed by a long recovery. Of his planned works, he was only able to write his book on the settlement of territorial-ethnic questions by international arbitration between 1968–74, but he could not find a publisher for it in Hungary. The book was finally published in England in translation in 1976, with the conspiratorial help of his friends Zoltán Szabó and András Révai, who lived there. He had no opportunity for more rest or quieter work after his retirement in 1971, the year his sister died and he became the sole caretaker of his mother. We know of his planned work from a letter he wrote to Zoltán Szabó and András Révai in London in 1968; of the topics listed in this letter, apart from The International Community of States… (A nemzetközi államközösség…), only one longer, tape-recorded reflection on the meaning of European social development was completed in a relatively elaborate form.

In the final years of his life he welcomed the renewed interest in his work. He agreed to publish his collected works with the European Protestant Hungarian Free University, registered in Switzerland.

On his seventieth birthday, his admirers in Hungary wanted to surprise him with a congratulatory volume, and had already begun to organise it when Bibó died of a heart attack on 10 May 1979, three weeks after his wife’s death. At his funeral, which was attended by hundreds of his admirers in the company of an appropriate number of secret police, Gyula Illyés spoke on behalf of his friends, and János Kenedi on behalf of his young admirers. The mourners expressed their feelings with a spontaneous singing of the National Anthem. By 1981, the tribute volume had become the Bibó Memorial Book, written by more than seventy authors without censorship or self-censorship. The publication of the volume was blocked by state-controlled publishers, so it was published as a samizdat, an illegal underground publication.

This was the beginning of the Bibó renaissance, to which the Kádár regime had to somehow react. The publication of the selected works of István Bibó, initiated by István Bibó Jr. in 1979, was finally realized in 1986.

The Bibó renaissance peaked in the late 1980s and early 1990s. After 1989, all political forces except the far right and the far left made frequent references to István Bibó, but these references gradually ceased. In the trench warfare of Hungarian political life, there is no ammunition to be found in Bibó’s works.

The biography was written by István Bibó Jr., translated by Benedek Totth and Austin Wagner.

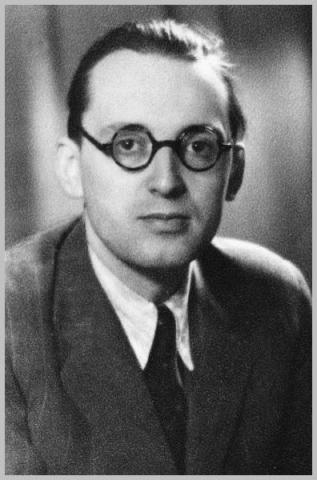

Bibó István, 1935 (Forrás: Wikipedia)

Bibó István, 1935 (Forrás: Wikipedia)