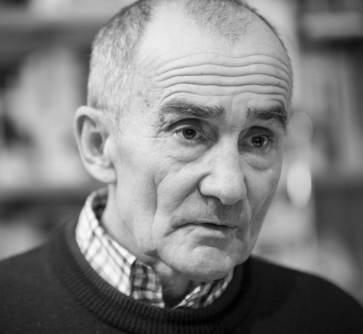

Marno János: Biography

János Marno (Budapest, 3 March 1949 –)

Attila József Prize-winning poet, writer, literary translator, art critic. Member of the Digital Literature Academy since 2017.

*

Born in Budapest on 3 March 1949. He spent his childhood in the small village of Piliscsaba. At the age of two, Marno’s family was displaced by the communist regime. The six of them lived in the kitchen of their host family. His father, Béla Marno, originally a lawyer and military officer, was imprisoned by the State Protection Authority in 1950 and sentenced to death in a show trial, but was released on amnesty in the summer of 1956. In October of the same year, their plan to emigrate to West Germany failed. János Marno’s mother, Hedvig Batta – who, after Béla Marno was taken away, was unaware of his whereabouts for two years – worked as a nurse when not spending time with her traumatised, often bedridden child. She listened to classical music with János and introduced him to her favourite books.

This period was crucial for Marno’s intellectual development, as he recalls that he was already preoccupied with the contradictory relationship between sickness and creativity. The 1956 Hungarian revolution was also a fundamental experience for him, as he told in a 2017 interview: „I could not forgive people for resigning themselves to the failure of the revolution, from that time onwards the only thing that held any water for me in Hungarian history was Rákóczi’s War of Independence, not ’48, and ’56 stuck in my throat. It was only after long, long decades that I could say that the survival instinct overrides everything. And let’s not forget that the youth novels of the time, and even the fairy tales, favoured absolute heroism, self-sacrificing heroism, and I was a bed-wetter under the spell of the pugilist.”

In 1970 he married Éva Forián-Szabó and they moved to Buda. In 1977, their first child Dávid was born, and in 1979 their second child Hanna was born.

With the move to Buda, the period in which he was significantly influenced by the Hungarian neo-avant-garde came to an end. He approached this period of his life by recalling the time he spent with the director and screenwriter András Matkócsik, who worked with him on the set of The Eskimo Woman Freezes (Eszkimó asszony fázik), and later with Tamás Szentjóby, Jenő Balaskó, and Miklós Erdély. At this time, collaborative work and improvisation played a larger role in Marno’s work, and the performative dimension is even more prominent in the „interludes” with Csaba Szíjártó and Matkócsik.

Regarding the emergence of Marno’s creative autonomy, he says: „for decades I was reluctant to be a poet without Csabi [Csaba Szíjártó], and even after that I felt for a long time that I was trying to write according to his style”. In line with this is the irony that one of Marno’s first texts, „Defloratio”, which was included in his debut volume Walking Together, was first published under Szijártó’s name in 1974, in the journal Magyar Műhely in Paris.

Thus it is shown that thinking and collaborating together can be of great significance in the practice of someone who is often thought of as a poet of separateness, of belonging nowhere. This is also important in later years: Marno inspired the members of the Telep (Colony) poetry group (2005–2009) at gatherings in the 2000s, led poetry workshops at the camps of JAK [József Attila Circle, an association of young writers] (2009), and worked as an external lecturer at the Pázmány Péter Catholic University.

The „great walks”, as he said in 2017, began in Bamberg, where he arrived thanks to the intervention of György Konrád (Bavarian State Scholarship, 2000–2001), but became really important in Budapest, in the Gesztenyéskert in the 12th district, for almost a decade and a half.

He worked as an editor for the Múzsák Publishing House from 1986 to 1989, and was editor of the literary column of Igen from the regime change until 1991. He was also a commissioner and an extra in operas.

He first published his poems in Mozgó Világ in 1980. In the 1990s, he published a book of essays, a book of prose, and five books of poetry, one of which contains selected and new poems. Eight books appeared following the turn of the millennium, including a collection of essays. Marno’s career is described in terms of „either/or”: although he started at the age of 38, he has been building his oeuvre with great consciousness ever since.

Marno is passionately interested in the malleability of mental and physical problems. His panic disorder, which developed in 1980–81, should not, he believes, only be seen in a negative light. He went to see an internist-cardiologist who carried out psychoanalysis, but no organ problems were diagnosed: „I owe a lot to these two and a half years, and therefore also to the panic disorder itself, because it made me see the absurdity and absurd reality of human existence”. But this was also preceded by a diaphragmatic hernia, as a congenital disorder – the problem of breathing can be described as a disease of the mind and body („psychic or enzyme problem”).

In his oeuvre, the paranoid attention to the functioning of language and the body sets his consciousness on a pathological radar, a problem detector. He repeatedly approaches his siblings and his relationship with them through various lay and/or medical diagnoses. If a train of thought is unfolding, it can easily turn out to be organised around, for example, the duodenal ulcer he got at the age of 23. From that point on, Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, which he read at the age of nine or ten, gave him the sanatorium air of literature.

Ever since then, it has been a question of how clear the X-ray vision of self-observation can be kept. His poetry is increasingly interested in how what is not visible at first sight relates to what is visible at first sight. The desire to create and observe layering leads to a widening of the „X-ray eye”. The theme of a Marno poem could be ambivalence itself. Or the „dramatic event: I denounce, and the poem eradicates my positions”, he wrote in a 1991 interview, and this position has remained unchanged ever since. Though perhaps not the experience of an opinion, but rather of „the will of the poem”, as he also puts it. But do Marno’s poems also eliminate Marno’s biography? His poetry rather devours the data. As if to convey that enumeration tells us too little about what is happening to us.

The biography was written by Miklós Borsik, translated by Benedek Totth and Austin Wagner.