Devecseri Gábor: Biography

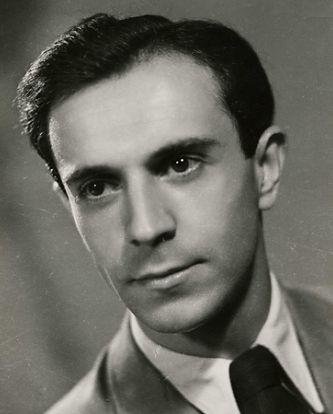

Gábor Devecseri (Budapest, 27 February 1917 – Budapest, 31 July 1971)

Kossuth and Attila József Prize-winning poet, writer, literary translator, classical philologist. Elected a posthumous member of the Digital Literature Academy on 4 June 2020.

*

Gábor Devecseri was born on 27 February 1917 in Budapest. His father, Emil Devecseri, was a lawyer and bank officer (1889–1951), his mother, Erzsébet Guthi (1892–1965), was a literary translator, and his maternal grandfather, Soma Guthi (1866–1930), was a well-known publicist and playwright of the turn of the century. (He recalls the memory of his first home in his poem On the corner of Lágymányosi Street and Bicskei Street (A Lágymányosi utca és a Bicskei utca sarkán). Devecseri’s family moved several times during his childhood, but they never left the neighbourhood, which is today the area around Bartók Béla Street.

He wanted to be a poet from an early age. In 1932, his first joint volume with Gábor Karinthy was published under the title Poems of Gábor Devecseri and Gábor Karinthy (Devecseri Gábor és Karinthy Gábor versei). The publication of the book was financed by Emil Devecseri and was reviewed in Nyugat, the most important literary journal of the era. However, it is likely that the attention paid to the surprisingly mature early poems was attributable to the authors’ parents. In his later reminiscences, Devecseri recalls in detail his memories of the famous poets he met in his childhood. This extended circle of poets and artists was the most important sphere of his literary socialisation. Around 1932, he sent his poems to Mihály Babits, the editor-in-chief of Nyugat, who, although he encouraged the young poet to continue writing poetry, did not publish his works in the journal until June 1935. His first independent volume, however, was published by Nyugat Publishing House in 1936 under the title The Merry Sea (A mulatságos tenger). Gábor Devecseri belongs to the third generation of the Nyugat.

He graduated from the Reformed Secondary School in Budapest (later the Lónyay Street Reformed Secondary School) in 1934 and worked as a private clerk for a year. In 1935, he enrolled in the Greek and Latin department of Pázmány Péter University, graduating in 1939. According to his recollections, the views of the distinguished classical philologists who taught at the university, and who were in constant debate with one another, shaped his thinking about antiquity. In 1941, he completed his doctorate, writing a dissertation entitled The Artistic Consciousness in the Poetry of Callimachus (A művészi tudatosság Kallimakhosz költészetében).

His choice of university and academic interests was primarily determined by his ambitions as a literary translator. His first major work was a translation of all the poems of Catullus into Hungarian, a bilingual collection with a foreword by Károly Kerényi, published in 1938. His interpretation, which reflected the influence of the ‘beautiful infidelity’, the translation tradition of Nyugat, was sharply criticised by an earlier translator of Catullus. Controversies surrounding the interpretation of ancient authors accompanied Gábor Devecseri, who had produced a work of extraordinary importance and scope, for most of his life, even though essential points of his professional principles changed in later years. He was awarded the Baumgarten Prize in 1939.

The poems of his next volume, the 1939 work entitled To My Friends (Barátaimhoz), already show the growing influence of the poetry of antiquity. In 1941, the second volume of Homer’s Hymns, translated by Devecseri, was published, and in 1942, the translation of Plautus’ comedies The Swaggering Soldier and Three Coins. In the same year, he published his verse comedy The Pseudo-Pet-Seller or The Triumph of True Love (Ál-állatkereskedő vagy Az Igaz Szerelem Diadala).

In 1941, he married Klára Huszár (1919–2010), who later became known as an opera director and translator. Their only child, János, was born in 1944. Gábor Devecseri worked as a librarian at the Baumgarten Library between 1942 and 1945. He was briefly conscripted during World War II, and he spent the final months of the war with his family in the capital.

Shortly after the end of the war, in August 1945, he published a collection of essays entitled The Living Kosztolányi (Az élő Kosztolányi), in which he analyses some of the works of his poet predecessor Dezső Kosztolányi, who he also knew personally. Still in 1945, he published a collection of poems he had been writing since 1939 entitled An Elegy of Margaret Island (Margitszigeti elégia), and a children’s poetry collection entitled Zoo Guide (Állatkerti útmutató). In the following year, a selection of his lyrical oeuvre was published in a volume entitled Letter from the Mountain (Levél a hegyről) and a collection of essays entitled Budapest Fairy Town (Budapest Tündérváros). In 1946 he was awarded the Baumgarten Prize for the second time. In 1946–1947 he worked as an assistant lecturer at the Institute of Greek Philology at Pázmány Péter University, while at the same time teaching art history at the Hungarian Academy of Theatre.

In 1947, he reached one of the most important stages of his career as a translator: his translation of the Odyssey published at that time is still considered the canonical Hungarian version of Homer’s epic. Gábor Devecseri’s method of literary translation had by then fundamentally deviated from his early works. In creating the language of the ‘Hungarian Homer’, he used elements of modern poetry (as can be seen, for example, in the frequent use of enjambements), but at the same time, formal fidelity and the precise and flawless application of tense were unquestionable principles of the translation. Also in 1947, together with Imre Trencsényi-Waldapfel, he published a collection of translations entitled Greek Poems (Görög versek), which was created with similar professional considerations to the Odyssey.

The turn in Gábor Devecseri’s worldview and conception of art coincided with the communist takeover of the country, which ended in 1948–1949. In the summer of 1947 he joined the Hungarian Communist Party, and from June 1948 he joined the Hungarian People’s Army, where he first worked as a literature teacher at a training academy, and later took part in the editing of cultural magazines published by the Hungarian Army. He was a member of the writers’ group of the People’s Army (with the rank of captain, major and then lieutenant colonel). Between 1949 and 1951 he also served as secretary general of the Hungarian Writers’ Association. In addition to his occasional poems, many of which were agitational, his literary manifestations of this period also mark a break with his earlier world view. His commentary on the Lukács debate in the 27 November 1949 issue of Szabad Nép is memorable, and contributed greatly to the success of the smear campaign against the philosopher György Lukács.

In 1950 and 1952 he was awarded the Attila József Prize. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, two collections of his poetry were published, Spreading Light (Terjed a fény – 1950) and Mirror of the Future (Jövendő tükre – 1954). In 1951, after the deterioration of relations between the Soviet bloc and Yugoslavia, he published a narrative poem in fourteen stanzas entitled Volunteer Border Guard (Önkéntes határőr), which drew attention to the importance of vigilance against the enemy lurking at the southern border. At the same time, he also became deeply involved in the art of Homer: in 1952 he published his other major work as a translator, an interpretation of the Iliad, for which he was awarded the Kossuth Prize in 1953.

After 1956, Gábor Devecseri turned away from public life. He left the poetry of the fifties spectacularly behind, and in his later memoirs he only tangentially mentions these years. For a time his attention turned to the theatrical genres: in 1957 he published an illustrated edition of his opera text based on the novel by E. T. A. Hoffmann (Student Anselmus [Anselmus diák]), and in the same year he completed his play The Loves of Odysseus (Odüsszeusz szerelmei). He submitted the text to the National Theatre under the title Island and Sea (Sziget és tenger), but the premiere did not take place until 1961 on the University Stage (the book version was published in 1964). In the meantime, he had been working on a series of translations, including ancient Latin and Greek, as well as English, German, French, Russian and even Persian texts of later periods (sometimes going off of rough translations by others). But the most important translation project of these years was the translation of all of Horace’s poems. Devecseri was one of the coordinators of this large-scale collective effort, which involved some seventy literary translators and poets of the period. The bilingual volume, the result of years of workshopping, was published in 1961. Devecseri wrote the book’s unusual afterword, in a playful manner and form reminiscent of Horatian poetry, describing the literary principles that the contributors sought to apply in the translation. The publication of the book was accompanied by a lively debate in the literary press.

Although he had been interested in Greek culture for decades, his first trip to Greece had to wait until the early 1960s: it was his experiences there that inspired his 1961 travelogue Homer’s Journey (Homéroszi utazás). Some of his important ancient translations of the 1960s include a collection of poems by Anacreon (1962) and a translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1964).

In 1967, he published his collection of essays, The Gods of Lágymányos (Lágymányosi istenek), in which he pays tribute to the idols and masters of his childhood and youth. The turn of the sixties and seventies was marked by a diversity of genres in Devecseri's oeuvre. In addition to his second travel diary to Greece, Epidaurus Crickets, Speak! (Epidauroszi tücskök, szóljatok – 1968), which partly reproduced earlier texts, he also published a collection of poems based on photographs by Ernő Vajda, Old Trees (Öreg fák – 1969), and an oratorio, A Bull’s Obituary (Bikasirató – 1971), the latter of which was staged by his wife Klára Huszár.

In 1970 he was diagnosed with cancer and spent the last nine months of his life in hospital. He continued to work, writing a libretto for Mozart’s Thamos, King of Egypt, and translating Menander’s Epitrepontes (‘Arbitration’).

He passed away on 31 July 1971, and a collection of his last poems recorded by tape-recorder, In Refutation of Transience (A mulandóság cáfolatául – 1972) was published posthumously. On his deathbed, he began another autobiographical work: The Advantages of Cutting the Belly (A hasfelmetszés előnyei). A few chapters were published in Élet és Irodalom before his death in 1974. The same year saw the beginning of the publication of Gábor Devecseri’s complete oeuvre, including his own works and translations.

The biography was written by Gábor Reichert, translated by Benedek Totth and Austin Wagner.