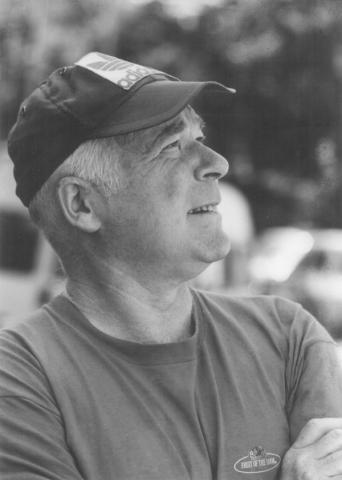

Moldova György: Biography

György Moldova (Budapest, 12 March 1934 – Budapest, 4 June 2022)

Kossuth Prize-winning and two-time Attila József Prize-winning writer. Founding member of the Digital Literature Academy since 1998.

*

György Moldova was born György Reif on 12 March 1934 in Budapest to a poor Jewish family. He and his family lived through the Holocaust in the Budapest ghetto. He completed his elementary school education at the Pongrácz Road School and his secondary education at Szent László Secondary School, but also worked as a manual labourer from a young age to support his brother, sisters and mother. In 1952, he was admitted to the Drama Department of the University of Theatre and Film Arts, but his studies were interrupted: although he passed all his exams in 1957, his planned play about the Rajk show trial was not accepted as a thesis. (He received his diploma later, in the 1980s.) For a few years he supported himself with manual jobs such as a boiler mechanic and a miner. In the late 1950s, he was employed as a dramaturge in the film industry – his popular theatre and film works (Love Thursday [Szerelmcsütörtök, 1959]; Please, Jeromos [Légy szíves, Jeromos, 1962]; Arrivederci, Budapest!, 1966) are partly associated with this period. He worked as a freelance writer from 1964.

He published his first short stories in 1955 in the magazines Új Hang and Csillag (during this time he took the pen name Moldova); his texts, which brought the world of quarry workers to life, attracted attention in the literary world, and his first collection of short stories, The Foreign Champion (Az idegen bajnok), published a few years later in 1963, as well as his subsequent works, also received critical acclaim. By the 1970s, due to his high-profile reports, popular satires, and his prolificness, he had become one of the country’s best-known and most widely read writers. His mixed-genre volumes, published year after year, have been widely acclaimed. In the 1980s, Magvető Publishing House launched a book series of his oeuvre.

As a private person, Moldova led a modest life, and the wider public knew little about his family life. His first wife was Zsuzsa Léhner, who gave birth to two daughters, Zsófia Moldova (1975) and Júlia Moldova (1977). After his wife’s death, he remarried to his editor, Katalin Palotás, in the winter of 2021.

But despite his popularity, he was also a controversial author. His isolation from contemporary literature, despite the early critical acclaim, began even before 1989, due to his own choices, human conflicts, and literary character on the one hand, and his works, which were independent of the canons of the time, and primarily aimed to meet readers’ needs, on the other. Most spectacularly, his 1988 police sociography, The Crime of Life (Bűn az élet), was the first to come under political attack for its one-sided portrayal of Roma criminals. Later, he garnered criticism for his role in the government delegation pushing for the construction of the Bős-Nagymaros power dam and for his book on the subject (Ég a Duna! [The Danube In Flames, 1998). From the 1990s onwards, he made an increasing number of statements in favour of the Kádár regime, and although his popularity among his readers remained unbroken, he became isolated from literary life and intellectual circles. His most controversial book (and one of his best-selling) was the two-volume monograph on János Kádár (2006), which was followed by a series of public political debates. From this period onwards, Moldova was less a contemporary writer and more a political opinion-former in the Hungarian public sphere – even in his last years, he made numerous statements on current political issues.

On Saturday morning, 4 June 2022, at the age of 89, he passed away at his home, surrounded by his family.

*

Short stories and novels

His first volume, The Foreign Champion, collected his short stories and short fiction published between 1955 and 1963. In this collection, the two distinctive strands of Moldova’s work in the field of prose are already clearly distinguishable: the short stories „Paul Kalina” („Kalina Pál”), „Mandarin, the Famous Vagabond” („Mandarin, a híres vagány”), „Frankie Devill” („Ördögh Feri”), and „Twelve Houses” („Tizenkét Házak”) are populated with characteristically drawn heroes of the suburbs, while the larger texts in the volume („The Destruction of the Holy Trinity” [„A Szentháromság pusztulása”], „Night Tram” [„Éjszakai villamos”], „Lonely Pavilion” [„Magányos pavilion”], etc.) foreshadow the themes and narrative style of later Moldova novels. While the continuation of the early short stories can be found in Moldova’s atmospheric, sociographic observations, we can mainly see them in his essentially anecdotal narrative (sometimes humorous, sometimes more satirical) short prose – for example, in Under the Gas Lamps [Gázlámpák alatt, 1966), the direction of the narratives depicting the social changes and political ruptures of the 1940s and 1950s through the fate of an individualistic hero was completed in the novel cycles published from the mid-1960s onwards.

Moldova’s first novel, Dark Angel (Sötét angyal), was published in 1964 and was soon followed by five more novels up to the mid-1970s. His works at this time are not only thematically related – most of them are set in Hungary in the 1940s and 1950s, and explore the war, the Rákosi regime, and the aftermath of the 1956 revolution – but also in terms of genre, poetics, characters and settings. The novels written in the narrow decade between 1963 and 1972 – The Lonely Pavilion (Magányos pavilion, 1966), The Mill in Hell (Malom a pokolban, 1968), The Legion Dismissed (Az elbocsátott légió, 1969), and The Guardians of Change (A változások őrei, 1972) – focus on a lonely hero in search of truth who try to assert themselves and find their place in the world amid the turmoil of changed social conditions with no social mobility and the political events of historical significance. All of these works fit into the genre tradition of the coming-of-age novel, while the plot is often enriched by elements of the love story or crime novel. The novels listed are so similar in terms of the themes they deal with and the types of heroes they portray that the characters’ relationships are usually recurrent: the most striking of these relationships is the love affair between self-sacrificing women who are unable to fulfil their potential in their work and private lives and men who are ambivalent, often selfish and self-righteous. As several of Moldova’s critics have pointed out: his novels are unsuccessful and oversimplified in themselves, their value lies more in the apt observations that emerge in well-done episodes, in the descriptions of reality that are presented with a narrow linguistic toolkit and that testify to an insight into the essence of the matter.

There is a contradiction between Moldova’s writing style, his choice of subject matter and genre, and his basic literary inclination, which is true of his entire oeuvre. While his interest in recent Hungarian history and his puritanical, realistic style are a testament to a profound need to explore reality, Moldova is in fact the archetypal writer of the great storyteller: the struggles of his everyday heroes (their inner psychological struggles and their mostly unsuccessful battles against the injustices of existence) take on a mythical perspective. As Ljubomir Bezdomen, the protagonist of the short novel The Foreign Champion, puts it: „I think the task of writing, and not only of writing but of all art, is to create a new myth of modern man.”

The most significant (and final) turning point in Moldova’s fiction was the historical parable Forty Preachers (Negyven prédikátor), published in 1973 to greater critical acclaim than his earlier work, which depicts the perseverance of 17th-century preachers who persevered in their imprisonment for Protestant ideas. Another novel from this period is the autobiographical novel of 1975, The Saint Emeric March (A Szent Imre-induló), which occupies a special place among Hungarian literary depictions of Hungarian Jewish life and the atmosphere of the Budapest ghetto, and which Moldova continued in 1981 with a novel entitled The Lingering Virginity (Elhúzódó szüzesség).

Moldova’s choice of themes and his prose-poetics did not take any new turns after the mid-1970s: although his later novels set in a recent historical or contemporary setting (The Fruit of Your Womb [Méhednek gyümölcse, 1986]; The Last Frontier [Az utolsó határ, 1990]; The Gate of Fear [A félelem kapuja, 1992]; Battle With the Angel [Harc az angyallal, 2015]; The Rearguard [Az utóvéd, 2016], etc.) do have varied or updated themes developed in the 1960s and 1970s; the motifs of the 1998 historical novel If the Angel Would Come (Ha jönne az angyal) recall Forty Preachers. By then, Moldova’s literary interests and working method were fixed: the experimental short prose of his early career was integrated into the sociographic tradition of the sixties, while at the same time being in tune with later developments in Hungarian prose literature (objectivity, literary postmodernism, etc.). This is of course also due to the fact that Moldova’s greatest successes were not his novels, but his entertaining satires, and even more so his reports that aroused the interest of the wider Hungarian population, meaning that from the turn of the seventies and eighties he was mainly regarded as a writer „specialising” in sociographic books. And, as his autobiography, The Pusher (A bolygató, 2014), shows, it was these that he was most proud of.

Satires, reports, sociographies

Moldova first began publishing satire in the second half of the 1960s, although his humorous, satirical, and often absurdist vision was already evident in his early short stories. His first satirical work was The Cursed Office (Elátkozott hivatal, 1967), which depicted the absurdities of socialist bureaucracy with unparalleled insight, creating continuity with such Hungarian literary authors as Kálmán Mikszáth and István Örkény. This corpus became one of the most significant parts of his later oeuvre: right up until his death he was publishing satire collections as well as selected and more recent sententious writings (humorous essays, aphorisms), of which The Talking Pig (A beszélő disznó, 1978) is the most memorable.

His most enduring works, however, are his successive reports and sociographies published in the 1970s. In 1967 and 1971, he published a volume of press reports (Rag and Gold [Rongy és arany], The Boatmen’s Song [Hajósok éneke]), while he gained national recognition with his urban sociography, A Tribute to Komló (Tisztelet Komlónak), which was published in the series Discovering Hungary in 1971. The book, which describes the peculiar development of the socialist mining town in Transdanubia, was followed by a series of sociographies and reports. Moldova wrote books about the textile industry, truck drivers, lawyers, and prisons in Hungary. His most significant works in this genre were The Complaint of Őrség (Az Őrség panasza, 1976) and the report on the railways, Who Was Caught by the Locomotive Smoke (Akit a mozdony füstje megcsapott, 1977), in which he spoke with sensitivity, criticism, and humour about the domestic winners and losers of the uneven social development and socialist transformation – writing about the fates of the individual rather than global, systemic contexts, as in his earlier novels.

Autobiographical writings

In the last phase of his career, from the 2000s until his death, Moldova published a number of autobiographical works. These works reflect both the ageing writer’s inner need to memorialise and summarise his life and his compulsion to contribute to the heated debates surrounding his person and to position himself in them. His first such work was Old Song (Régi nóta, 2002), followed in 2004 by The Last Bullet (Az utolsó töltény), a series of thirteen volumes of autobiographical fragments. This series is much more than Moldova’s own (fragmented) life story: it reports from a specific perspective on the defining events of 20th century Hungarian history and their social roots (in synchrony with the author’s reflections on the writing process, i.e. the years between 2004 and 2021), and also sheds a special light on the situation of the Hungarian Jewry and the dilemmas of the relationship to Jewish identity in the 20th century and today.

Moldova’s books published in the 2010s include The Sacred Ball (A szent labda, 2012), a confession about Hungarian football, Heads or Tails (Fej vagy írás, 2015), a work on the art of writing, and The Pusher (A bolygató, 2014), in which he sought to account for his successes, failures, human conflicts, and the controversies surrounding his person, publishing, and among other things, some of his observation files from the 1970s and 1980s. From these latter works, we can reconstruct the old writer’s long-established world view, mentality, and moral perception, and we can also get an idea of Moldova’s wide-ranging education and his human and creative relationship with the greats of Hungarian and world literature.

The biography was written by Dániel Szabolcs Radnai, translated by Benedek Totth and Austin Wagner.