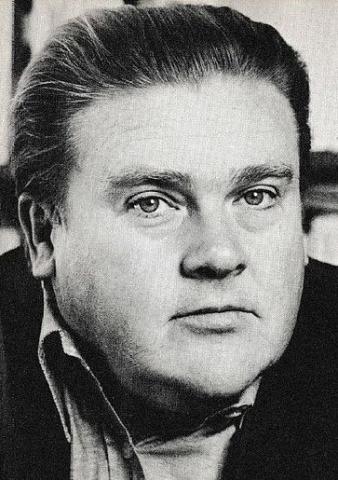

Csurka István: Biography

István Csurka (Budapest, 27 March 1934 – Budapest, 4 February 2012)

Two-time József Attila Prize-winning writer, dramaturg. Elected a posthumous member of the Digital Literature Academy on 4 June 2020.

*

István Csurka was born on 27 March 1934 in Budapest. His mother was Erzsébet Bodnár and his father Péter Csurka (1894–1964), who was also known as a novelist and publicist, first in the 1930s and then, after almost two decades of silence as a writer, at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s.

After the annexation of Northern Transylvania to Hungary in 1941, the family moved from the capital to Oradea (Erzsébet Bodnár was of Oradea origin). From 1944, they temporarily sought refuge from the war front in Budapest, then in Csepreg, and for a short time in Lichting, Bavaria. After the end of the war, the authorities refused to allow his father to move back to Budapest, so the family settled in Békés, Péter Csurka’s hometown. István Csurka continued his education there, graduating from the town’s prestigious high school in 1952. In the same year, he was admitted to the dramaturgy department of the Academy of Theatre and Film Arts, where his teacher was Gyula Háy. The memories of the college and the experience of alienation when moving (back) from the countryside to the capital are recalled in some of the short stories in the 1972 volume Out in Life (Kint az életben), specifically Four Storks (Négy gólya); Main Wall (Főfal); From Grooming to Grooming (Tisztálkodástól tisztálkodásig); Disturbances in the Infirmary (Villongások a betegszobában); and Out in Life (Kint az életben).

His earliest writings appeared in the periodical Sirály, compiled and edited by students at the college. His prose-writing talent was honoured by his teacher, and later author of Who Will Be the Belle of the Ball? (Ki lesz a bálanya?) Czibor János, who was the first to notice Csurka’s talent as a prose writer, and who published his first serious work, a short story called Nuptial and Slap (Nász és pofon), set in a dormitory environment, in the 1954 issue of the magazine Művelt Nép, where he edited. This, along with another early short story, Testament (Testámentum), was included in the 1955 anthology The Inauguration of Man (Emberavatás), which featured young prose writers. The publication of Nuptial and Slap in this edition generated a minor ideological controversy in the press: one review criticised the young author for his inadequate portrayal of the ‘socialist morality’ of rural youth. The fundamental social reorganisation of the post-1948 period, and the effects social mobilisation from the countryside to the capital had on the individual, were important themes in Csurka’s early works. The first collection of his short prose texts was Fire Jumping (Tűzugratás), published in September 1956, but its reception was soon halted by the events of the Revolution of 1956.

At the school meeting of the College of Theatre and Film Arts on 27 September, István Csurka gave a strong speech summarising the students’ demands regarding reform of art education. On 23 October, he was one of the organisers of a demonstration at the college, and on 28 October he was elected head of the national guard at a youth hostel, but did not take part in the armed fighting. He was arrested for his involvement after the revolution was crushed in March 1957 and interned to Kistarcsa in April. He was allowed to leave the internment camp at the end of August, where he signed a recruitment document for the state security authorities in exchange for his release (he chose the code name ‘Raskolnikov’), but after his release he refused to cooperate in any meaningful way, and was excluded from the network by the state security service in 1963. Csurka himself publicized the documents of his recruitment and refusal to cooperate in 1993, while still a member of parliament, in the wake of the internal strife in his party, the MDF. In his ‘dry novel’ The Aesthete (Az esztéta), published in 2006, he recalls in even greater detail, with additional documents, the history of his decades of surveillance, including the manipulative games he played with his keeper (ironically named as the aesthete). According to documents uncovered by the Interior Ministry, István Csurka was under almost continuous surveillance by Hungarian state security for almost three decades from the late 1950s.

After his release, he was allowed to obtain his degree at the college without any exams. He re-emerged in the literary public eye with a story entitled Dwellers and Buffoons (Lakók és ripacsok), published in the January 1958 issue of Kortárs. The real comeback, however, came with his first novel, False Witness (Hamis tanú), published in 1959. The story of László Bojtor, a teacher who was transferred to a village after graduation, paints a pessimistic picture of the possibilities of closing the gap in living standards between rural and urban life, of the adaptability of ‘modern life’. Although the novel is not without inconsistencies, its narrative technique, which was unusual for the time – the text is built up from the characters’ monologues, which are constantly alternating – already demonstrates the virtues of Csurka’s later prose, the twisting plot and the authentic depiction of the vernacular.

Until the fall of Communism, István Csurka worked as a freelance writer. He consciously built up the image of the ‘tough guy’, who was at home in the ‘bohemian world’ of the time, in the ‘deep waters’ of the Hungária café and other restaurants, and who risked his ample financial remuneration for his artistic activities at card parties and the racecourse. He used the latter designation to describe himself in a series of feuilletons he published in Magyar Nemzet in the 1970s and 1980s, selected pieces of which can also be read in the volumes Double Sausage (Kettes kolbász – 1980) and Passengers (Utasok – 1981). The lifestyle, which seemed defiantly decadent in the early Kádár era and which, according to reports to the state security services, aroused suspicions of ‘existentialism’, became the subject of many of his works from the 1960s onwards. The characters in his second collection of short stories, 1964’s Extension One-oh-Five (Százötös mellék), are typically amoral characters who are alienated from the Hungarian public conditions of the time while simultaneously exploiting them, motivated mainly by the satisfaction of their physical desires and gambling passions, and by the pursuit of material gain. The most memorable pieces in the volume are The Soul of a Punter (Egy fogadó lelkivilága),We Are from the Radio (A Rádiótól vagyunk) and Why Hungarian Films Are Bad (Miért rosszak a magyar filmek?). The latter was made into a film in 1964 by Tamás Fejér based on Csurka’s script. The 1972 volume As You Are (Így, ahogy vagytok!), co-written with Gergely Rákosy, introduces the strange socio-cultural world of horse racing. Apart from two short stories (Moór and Paál [Moór és Paál –1965]; Wallowing [Dagonyázás – 1985]), the short story was the representative epic genre of Csurka’s fiction (other collections include Horses are Human too (A ló is ember 1968); Nuptial and Slap (Nász és pofon – 1969); Out in Life (Kint az életben – 1972); The Soul of a Punter (Egy fogadó lelkivilága – 1976); Existence-technique (Létezés-technika – 1983) – the latter as part of a series of his life’s work published in the first half of the 1980s.

His theatre and film career in the early 1960s established his widespread popularity, and a few years later he was one of the most sought-after Hungarian writers. In addition to Why Hungarian Films Are Bad, he also wrote the screenplays for films such as The Street of Garden Houses (Kertes házak utcája – 1962), What’s New in Pest? (Mi újság Pesten? – 1969), Seven Tons of Dollars (Hét tonna dollár – 1974), The Sword (A kard – 1977) and American Cigarette (Amerikai cigaretta – 1978).

Considered one of the major works of his career, his drama Who Will Be the Belle of the Ball? was written in 1961, the year of János Czibor’s suicide, and his characters were modelled after members of his own circle of friends. The chamber play, which begins lightly but becomes increasingly lethargic, tells the story of a night of overplayed cards which suggests the general despair of the early Kádár era, and for a long time no theatre staged it. However, it quickly became known in intellectual circles, and Zoltán Várkonyi, then director of the Vígszínház, asked Csurka to write first Boaster (Szájhős – 1964) and then The Ravages of Time (Az idő vasfoga – 1965). In 1971, the utterly pessimistic Deficit was performed in Pécs, and in the same year Csurka produced a stage version of Moór and Paál, which was presented as Dead Mines (Döglött aknák) with overwhelming success. In the meantime, Who Will Be the Belle of the Ball? had also been staged, premiering at the Thália Theatre in 1969. In the seventies and eighties, in addition to the earlier ones, several of his new plays were staged by theatres in Hungary: Original Location (Eredeti helyszín – 1976); Big Cleaning (Nagytakarítás – 1977); Competition Day (Versenynap – 1977); Mourning for the Caretaker (Házmestersirató – 1978); May Day (Majális – 1980); Reciprocal Comedy (Reciprok komádia – 1982); Exams and Disciplines (Vizsgák és fegyelmik – 1988); Lasting (Megmaradni – 1988), etc.

He was temporarily banned from publishing and performing his works twice before the regime change. In 1973, he was investigated by the Writers’ Union and prosecuted by the police and the public prosecutor’s office for his scandalous behaviour in the Szigliget Creative House and for his anti-Semitic statements. The case resulted in a year-long silence, with the relief that the Katona József Theatre did not remove the play Dead Mines from its repertoire. His second silence took place in 1986, for his contribution to the reading of his performance of The Bloody Sword (A véres kard) on Radio Free Europe on 15 March in New York, and the publication of his collection of essays, The Unacceptable Reality (Az elfogadhatatlan realitás), by Püski Publishing, also based in New York.

Since the late 1970s, he took an increasingly active stance on public issues. His name was among the signatories of the Charter of ’77, his essay appeared in the Bibó Memorial Book of 1980, and in 1983 he took a stand with Sándor Csoóri, who was sanctioned by the authorities for his foreword to Miklós Duray’s book Tight Corner (Kutyaszorító), published in New York, by demonstratively leaving the Writers’ Union. He participated in the 1985 Monor and 1987 Lakitelek meetings. A founding member of the Hungarian Democratic Forum, he was a leading figure in the popular wing of the regime-change intelligentsia. From 1990 to 1993, when he was expelled from the party, he served as a member of parliament for the MDF. In 1993, he founded the radical right-wing Hungarian Justice and Life Party (MIÉP), which ran a parliamentary faction between 1998 and 2002, and he remained its chairman until his death. His political career after the fall of communism overshadowed his fiction writing, with one of the few exceptions being the 2005 volume of older and more recent short stories entitled Festival Tomcat (Fesztiválkandúr). Political journalism became his leading genre, with the Magyar Fórum and the Havi Magyar Fórum as his main publications. His work as a journalist, which runs in the thousands of pages, is as much contested as his work as a politician. The rhetoric of his articles and public speeches, and his anti-globalist argumentation, steeped in anti-Semitism, have been heavily used by the domestic far-right movements of the last three decades.

His last two plays, The Sixth Coffin (A hatodik koporsó) and The Wars of the Writers’ Unions (Írószövetségek harca), were published in 2011.

He died on 4 February 2012 in Budapest.

The biography was written by Gábor Reichert, translated by Benedek Totth and Austin Wagner.