Csengey Dénes: Biography

Dénes Csengey (Szekszárd, 24 January 1953 – Budapest, 8 April 1991)

Attila József Prize-winning writer. He was elected a posthumous member of the Digital Literature Academy on 4 June 2020.

*

Born on 24 January 1953 in Szekszárd. He completed his primary school education in Szekszárd and also began his secondary education in Szekszárd, but finished it later in Budapest.

After graduation, he supported himself with various odd jobs: car mechanic, warehouse worker, insurance agent, manual laboror.

Between 1973 and 1975, he completed his obligatory two years of military service. In the meantime, his first writings were published in a county newspaper, in a column for young authors.

After he was discharged from the army, he was employed as an unqualified daycare and art teacher in a primary school.

It was not until 1977, at the age of 24, that he enrolled at the University of Debrecen, where he studied history and literature. He graduated as a secondary school teacher in 1983.

In the meantime, since 1978 he published regularly in various journals, including Alföld, Mozgó Világ and Életünk.

The year 1980 brought about major changes in his life. He received a Zsigmond Móricz scholarship, which alleviated his persistent financial problems. He married Melinda Ferencz, whom he met at university. In the same year, their first son András was born.

He was involved in various movements and organisations of young intellectuals as early as his university years. In 1981, he joined the Attila József Young Writers’ Circle (FIJAK), where he was a member of the board from 1982 to 1985 and secretary from 1983 to 1984.

After graduating in 1983, he worked as a freelance writer and published his first book „…és mi most itt vagyunk” (‘...and we are here now’), a generational essay on songwriters Tamás Cseh and Géza Bereményi.

In 1984, his monodrama A cella (The Prison Cell) was staged at the Katona József Theatre in Kecskemét. In the same year he moved with his family to Keszthely.

He took an active role in the political life that began to revive in 1985. He was present and even spoke at meetings of the political opposition. His second son Balázs was born.

He took part in the opposition meeting in Lakitelek in 1987, and with nine of his colleagues founded the Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF), of which he was a parliamentary representative from 1990 and a member of the board until his death.

He continued his literary activities in addition to his political work, and was a member of the editorial board of the Hungarian Writers’ Association from 1987 until his death, and of the Hitel journal from 1988. He also appeared in films as a supporting actor and wrote lyrics. Two of the most notable movies he took part in are Miklós Jancsó’s Szörnyek évadja (Season of Monsters – 1987), and Ferenc András’s Vadon (Wilderness – 1989.)

On 15 March 1989, as a keynote speaker of the opposition protesters, he symbolically took possession of Hungarian Television on behalf of the Hungarian people.

On 8 April 1991, aged just 38, he died of heart failure in his Budapest apartment.

*

The sovereignty of Dénes Csengey’s creative personality is evident not only in the diversity of his choice of forms, but also in his particular approach, which is difficult to separate from its political implications.

The period of his intellectual maturation coincides with the political changes of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The earth-shattering events that upset the entire map of Central and Eastern Europe greatly influenced his thinking, and vice versa – the need for change that was at the core of his being influenced the way regime change was implemented in Hungary in very concrete ways. His political engagement and literary work are in service to the same voluntary mission: to bring about reform.

In its spirituality and linguistics, belonging to a cultural community is expressed with irrefutable force. His character, his way of thinking, is incompatible with the kind of writerly engagement that is stuck at the level of the ‘artisan making artwork’. For him, the betterment of the country is a prophetic task and, as such, the only way to go. The role of the prophet, which tends towards romanticism and seems anachronistic in the 20th century, is the closest thing to it.

He feels that l’art pour l’art literature is a luxury. And even if an authoritarianism that does not tolerate resistance and demands the servitude of power may force the private individual into the underground, the artist can always find – and in Csengey’s case found – his ‘struggle for freedom’, fought with alternative, ingenious linguistic means. He affirms that the man of the spirit cannot ultimately be prevented by any violent method from confronting the system. The cultural cordons erected by censorship mark out for him individual and unique paths of associative, metaphorical, and yet sovereign thought and speech. To be on one side or the other of the ideological guardians of political tolerance as a point of reference: to take a firm stand. The climate of persecution leaves little alternative.

As he became more and more committed to political work, his writings on public issues multiplied. These appear in a volume titled Mezítlábas szabadság. Esszék, beszédek (Barefoot Freedom. Essays, Speeches) published in 1990. His writings go through a narrative metamorphosis, from their first attempts at flight to the discovery of mature creative forms. Initially, he used his mythology-inspired fiction as a veiled ‘discourse’ on public issues, but as his political career progressed, he used the tools of literary fiction to illuminate the prosaic, profane public narrative.

His political, literary and literary-political insights did not fit neatly into any artistically delimitable framework, and he was forced to use newer and newer means of genre variation and methods of objectification. It is impossible to project his oeuvre onto a single plane, to give it a single, unambiguous interpretation, since there are deep methodological gaps between the ‘languages’ belonging to it. Csengey’s peculiar view of the world, his conception of the interpretation of reality, almost forms a bridge between them.

Although Csengey was not particularly concerned with the literary zeitgeist, his epic symbolism also found its place among contemporary paradigms: in the case of bold transgressions between forms, with postmodernist attempts at associative imagery, and in its directions, with a reaching back to the archaic classicist formal icon. And this dualism in the creative text interacts with a reality that has been experienced and taken possession of by action.

His personality and his oeuvre are characterised by a concentrated strength and, consequently, by a deep suggestiveness. On the other hand, his writings sometimes risk being over-explained, which sometimes leads to over-complications. He is unable to remain objective. It is the multiple layers of reflection that make his prose both free and paradoxically complex. At the same time, his unique talent is demonstrated by his skilful use of narrative devices – the disruption of chronology, the shifting perspectives of his characters, the reflexive allusions to self-interpretation, the language of the utterances, the technique of omission, and the interweaving of a peculiar and multi-layered system of metaphors. At the same time, his stories always contain autobiographical references, sometimes direct and sometimes metaphorical, the intermingling of the personal and the fictional, the biographical and the literary self, real and imaginary time. This is true whether he is writing a novel, short story, essay, study, diary, film script, song lyrics, open letter or political speech.

Apart from his earliest experimental writings that were published in journals and anthologies, his first public appearance as a writer was in 1983. That was the year in which his „…és mi most itt vagyunk” (‘...and we are here now’) essay on social psychology was published, and the following year he staged the monodrama A cella (The Prison Cell) at the Katona József Theatre in Kecskemét.

This was an unusual start for a young writer: although he tried his hand at his own literary devices, he also tried to write in unfamiliar genres. The two works seem to have nothing to do with each other, because the former deals with the beat generation, the latter with a ‘poet prince’ who lived several centuries earlier. But in the deep layers of both works, we are dealing with a harsh social critique, an examination of the historical experience of a generation. Csengey uses the methods of psychological analysis to analyse community processes, comparing particular political and ideological constructions with social thought and the resulting forms of behaviour. He sought to reconcile socio-historical relations and to map and articulate the historical experiences that emerge from self-definition at the individual and community level.

In the second half of the 1980s, his work in various genres appeared at a rapid pace, but almost without exception they dealt with the question of generation: Villon’s monodrama, A cella (The Prison Cell – 1984); his songbook for Tamás Cseh, Mélyrepülés(Low Flying – 1986); his collection of short stories, Gyertyafénykeringő (Candlelight Waltz – 1987); his essay collection A kétségbeesés méltósága (The Dignity of Despair – 1988); and his novel Találkozások az angyallal (Encounters with the Angel – 1989). These were clearly his most productive years: he also worked as a literary organiser, helping to found the party, the Hungarian Democratic Forum, organising a referendum and taking part in the everyday political battles that preceded the first free parliamentary elections.

Csengey’s unexpected and untimely death in the spring of 1991 cut his life’s work in half, but his work has continued to have an impact on the cultural scene ever since.

Just before his death, he started to write a film script that was inspired by his disappointments with the regime change.

Az utolsó nyáron (In The Last Summer) is a symbolic work, the fulfilment of a project the author had been cherishing for years. Csengey did not live to see the film completed. The generation portrayed in this work, previously helpless under the conditions of dictatorship, is now left without a handhold in the boundlessness of freedom, and once again seems helpless.

Dénes Csengey’s short creative career was one of prohibition and urgency. A large part of his oeuvre remained either in the desk drawer or, better yet, on the pages of various periodicals. An attempt to remedy this, Szegényen, szabadon, szeretetben (In Poverty, in Freedom, in Love – 2003) was published, a volume that takes its title from a piece that Csengey wrote for a daily newspaper on Christmas 1989. The three expressions in the title, which are dominant and intertwined in the author’s oeuvre, can also be interpreted as a motto for a creator and politician who was deeply concerned about the fate of his country.

The biography was written by László Bartusz-Dobosi, translated by Benedek Totth and Austin Wagner.

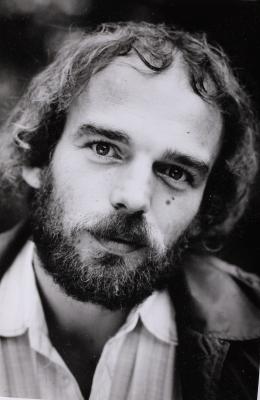

Csengey Dénes (Fotó: Csigó László)

Csengey Dénes (Fotó: Csigó László)