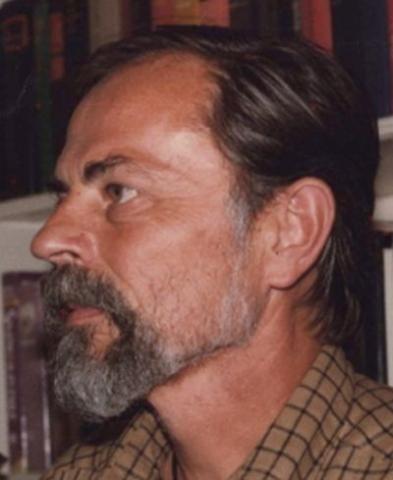

Csalog Zsolt: Biography

Zsolt Csalog (Szekszárd, 30 November 1935 – Budapest, 18 July 1997)

Attila József Prize-winning writer, sociographer, sociologist. He was elected a posthumous member of the Digital Literature Academy on 4 June 2020.

*

Zsolt Csalog was born Zsolt András István Csalogovits on 30 November 1935 in Szekszárd. His father, József Csalog, shortened their surname, which he considered too Slavic-sounding. His mother, Márta Gaskó, had planned to become a singer in Stuttgart, but eventually gave up her dream and found her lifelong vocation in caring for her family. The archaeologist and museum director’s family belonged to the elite of the small-town middle class intellectuals, and the child testing out his wings did not feel at home in this snobbish, bourgeoisie environment. He was bothered by the formalities and constraints, the emptiness and meaninglessness of social life, but was nonetheless respectful and obeyed the rules. World War II and the years that followed opened up the world to him. After his father was B-listed (B-listing: a method of politically motivated ‘cleansing’ in Hungary between 1945 and 1947, aimed at removing from the public sector those deemed politically untrustworthy) the family moved to the Southwestern part of the country, where they lived among brickyard and sawmill workers, learning from old-timers about the natural way of life. From that time onward, his observance of rules was limited to those he considered reasonable.

From 1947 he attended the Jesuit boarding school in Pécs which was to determine his later values. After the takeover of church schools by the communist regime in 1948, Csalog was sent to a grammar school on the outskirts of the city. It was then, at the turn of 1947–48, at the age of 12 or 13, that he decided to resist at all costs the anti-democratic ‘order’ that was looming over him and threatening his existence. As a high school student, he spent his summers in the illegal Catholic youth movement and the scouts, mainly in Keszthely, where his father was posted. In 1951 he and his family moved to Jászberény, where he graduated from high school in the spring of 1954, and from there he was admitted to the Faculty of Arts at the University of Budapest in the mid-fifties.

During the 1956 Revolution, while still a university student, he took part in the fighting, including the siege of the radio’s headquarters, the source of state propaganda. Somehow, his presence in the fighting was overlooked by the authorities, so his involvement in the revolutionary events had no direct consequences for him. He graduated in 1960 with a degree in history, ethnography, and archaeology. At university he met his wife and eventual mother of his children, ethnographer Éva Pócs. In the same year they moved to Szolnok with their first-born child, the later world-famous pianist Gábor Csalog. Although he only took up archaeology for his father’s sake, Zsolt Csalog took part in numerous excavations and regularly published articles on the subjects of his research.

Their second child Anna died in 1964 and they moved to Budapest in 1965 to have their third child. Csalog became a staff member at the Museum of Ethnography. He started writing short stories in the mid-1960s.

His short stories were initially published in the journal Új Írás. In his first years in Budapest, he participated in collection work for the Hungarian Ethnographic Atlas, in exhibition arrangements for the Museum of Ethnography, and also worked for the Central Statistical Office before he finally switched to drawing illustrations for specialist books, often as a substitute for his literary income. The last activity he continued until the end of his life.

In August 1964, police began the ‘operative processing’ of Zsolt Csalog. In June the following year, two men appeared at the archaeological excavation site where Csalog met the 42-year-old Lajos Mikluszkó, the narrator of his short novel M. Lajos, 42, and was taken to the police station. As it turned out, it was the Csalog couple’s 1963 trip around Europe that was the cause of the three-year-long harassment campaign against them. While visiting Éva Pócs’ relatives in Belgium, they came into contact with Father István Muzslay, who was active at the University of Leuven, and who tried to organise and promote the scholarship and education of young Hungarians (mainly those who took part in the 1956 Revolution and the fight for freedom) who were hindered for political reasons. They promised that after they returned him, they would continue their correspondence and offer their own personal suggestions to help the scholarship programme. The first police interrogation was soon followed by others, and the cornered Csalog was forced to write reports for the police. The couple were expecting their third child, Benedek. Csalog knew what he was risking. After revealing his situation to his wife, they fought side-by-side to preserve their integrity and their livelihood. In April 1968, during another interrogation, Csalog announced that he would not appear at any more meetings and readily signed a form admitting that he had become an ‘enemy of the Hungarian People’s Republic’.

In December 1970, 9 months after the birth of his daughter Eszter, he was approached by sociologist István Kemény, who asked him to join the then-forming workgroup researching the Gypsy minority group. The next day, Csalog resigned from his job at the Ethnographic Museum and went to work with Kemény. ‘That was the smartest decision in my life,’ he later said in a portrait film about himself. He learned the science of sociology – especially the particular way of thinking that radiates from the depths of his later fiction – on the fly, in István Kemény’s empirical workshop. In the meantime, his first collection of short stories, Tavaszra minden rendben lesz (Everything Will Be Alright by Spring), was published in 1971, but M. Lajos, 42 was blocked by the censors. The documentary portrait of Lajos Mikluszkó, who had visited the Gulag, was circulated in manuscript form, in samizdat, from then until its first legal publication in 1989.

Following an examination of its initial results, the Ministry of the Interior closed down the Gypsy research, the participants were let go, and Kemény was first banned from publishing, then forced to emigrate. In 1976 Csalog published his first sociography on the Roma people, Kilenc cigány (Nine Gypsies). In January 1977, together with more than thirty Hungarian intellectuals, he signed the Charter ’77 declaration initiated by János Kenedi. After that he found himself in an even more dire situation: from then on he too was subject to having his publications banned. At the same time – as he would later say about this period of his life – he felt like a free man, and unlike many, he held his head high and lived with a clear conscience.

In 1975 he divorced his wife, lived for a short time with his sociologist colleague Mária Magdolna Matolay, and after the break-up he remarried, this time to actress Anna Károlyi.

In the summer of 1971 – while doing field work – he met the eventual narrator of his later work, the Parasztregény (Peasant Novel), Eszter Muka, who, despite having completed three and a half civil classes and even having travelled to England to visit the grave of her son who had died abroad and her granddaughter who was born there, was an ‘unadulterated peasant woman’ in her way of life. It soon became clear that they needed each other: the desires of the peasant woman who had been preparing all her life to write her novel were in perfect harmony with the plans of the novelist who was looking for a subject for his novel. Csalog immediately saw the potential heroine behind Eszter’s story, and vice versa: Eszter found in Csalog the writer she had sorely needed. And the result speaks for itself: ‘Between the summer of 1971 and the spring of 1974, I recorded more than ninety hours of conversations with Eszter’, he writes in the afterword, Notes to the Peasant Novel, of the second edition of the novel, published in 1985.

At the same time, the publication of his works was cumbersome and slow, his books were printed in very small numbers and were not well-received by official critics. According to Csalog, his works were already ‘forgotten books’ at the time of their publication. His existential problems remained persistent and unchanging at this time. It was therefore a great pleasure when he was commissioned to do the graphic design for the representative publication Törzsi művészet (Tribal Art), published in 1981. With the fees earned for his Pointilism ink drawings, he bought the farmhouse in Vértesacsa, which later became his favourite place of residence.

In 1982, exhausted by a relentless press campaign against the decades-long research-based book of workers’ portraits, A tengert akartam látni (I Wanted to See the Sea), he travelled to the US on a Soros Foundation grant. Between 1985 and 1989 he lived in New York with his third wife, Agi Clark. By arrangement, however, he spent a few months each year at home, using his cassette recorder to collect material for his forthcoming books. Many of his works were only legally released in Hungary in 1989: Börtön volt a hazám (My Homeland Was a Prison), his portrait of István Hosszú, the hero of the miners’ strike in the Zsil Valley; Egy téglát én is letettem (I Too Laid a Brick) and Doku 56, his portraits of cadres and ’56 revolutionaries; and Fel a kezekkel! (Hands Up!), a sociography on the fate of foster care children who became pimps, whores, policemen and criminals.

Following the regime change in 1989, Csalog moved back to Hungary for good. ‘Now things are happening in Eastern Europe, and I have to see it,’ he said. Meanwhile, in 1988, he helped found the Alliance of Free Democrats. In 1989–90 he worked for the Magyar Napló and Igazság, but also published regularly in Hiány, Élet és Irodalom, Népszabadság and Kritika. He became a trustee of the Raoul Wallenberg Association in 1992 and its president in 1993–94. On 11 July 1993, as a speaker at the anti-fascist demonstration in Eger, he told his Roma brothers and sisters: ‘Fear not, Gypsies, the Hungarians have come!’

In 1993, he left the Alliance of Free Democrats. He was at odds with the party leadership on a number of important issues, after the party had given him an ultimatum: party membership, or the Gypsy matter. For Zsolt Csalog, this was not a moral choice: he stood up and left the party he was a founding member of. This was extremely traumatic for him.

From 1993, he worked as a researcher at the Social Services Centre and Institution of Budapest. During this time, he conducted interviews with homeless people which were later published in his posthumous volume Én győzni akarok! (I Want to Win). During this time a plan for a Roma Civil Rights Foundation was developed and later implemented with the support of the Soros Foundation. The plan for the Roma Press Centre, founded in 1995, was already on the table at that time, and Csalog became its first director. Despite the job being quite tedious, he loved it dearly, because after decades of isolation from the podium, he could finally teach: he could train young Roma to become professional journalists. It was during this time that the idea for what was to become Radio C was born, and it was also during this time that he had the honour of leading a writing workshop seminar at the Faculty of Humanities on Eötvös Loránd University.

Towards the end of his life, his love of the countryside came again to the fore; he preferred to stay at his house in Vértesacsa. In 1995 he married Éva Bognár and continued to work in spite of his declining health and the lung cancer he was diagnosed with in May 1996. He lived to see the premiere of the dramatised version of his homeless portrait Csendet akarok! (I Want Silence) in October 1996, and received the Central Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Hungary on his hospital bed.

He died in Budapest on 18 July 1997.

The biography was written by Márton Soltész, translated by Benedek Totth and Austin Wagner.