Daday Loránd: Biography

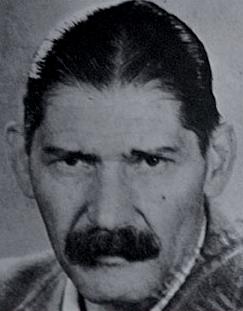

Loránd Daday (Beszterce, 6 November 1893 – Dés, 23 July 1954)

Writer. Elected a posthumous member of the Digital Literature Academy on 4 June 2020.

*

His father was Dr. Ferenc Daday, a prosecutor, and his mother was Jozefa Minichreiter. He had three brothers. He completed his elementary education in Dej, and his secondary studies at the Reformed College of Cluj, where he graduated in 1913. Between 1913 and 1917 he was a student at the Reformed Theology of Cluj and also the Faculty of Humanities of the Royal Ferenc József University. In World War I he served in the army from 1917, and was taken prisoner of war in Italy, from where he was released in 1920. In September 1920, he passed his pastoral qualification examination. He briefly served as an assistant pastor in a Transylvanian parish.

Between 1920 and 1924, he continued his studies at the Faculty of Arts of Pázmány Péter University in Budapest, where he obtained a doctorate in philosophy in 1924. In the meantime, he served as secretary of the Reformed Universal Convention. In the early 1920s, he published articles, studies and cartoons under his own name in Napkelet and Pásztortűz.

In 1925 he returned to Transylvania, having inherited a small estate from his uncle. Due to the difficulties connected with farming, he was temporarily cut off from literature. However, the Balkan authorities and the violent manipulations of officials, which were being established in the wake of the change of regime, encouraged him to write.

His first novel, Zátony (Reef), published in Budapest in 1930 under the pseudonym Mózes Székely, caused a storm not only in literary but also in political circles. His next novel, Thursday (Csütörtök), was published in 1935, also under the name of Mózes Székely, there was a witchhunt fueled by the press over the French edition of Reef, and he was sentenced to six months in prison by military tribunal for ‘insulting the sovereign in writing’. And this was despite the fact that he was defended by Victor Eftimiu, a representative of the Romanian PEN Club, as well as by the former Romanian Prime Minister Alexandru Vaida-Voievod. He served his sentences in the Brasov and Dej prisons. In the Dej prison he came into contact with communist prisoners and, on his release, he approached the left-wing magazine Korunk, where some of his short stories were published in 1936 under the name of Mihály Derzsi.

In the spring of 1939, following threats from the Iron Guard, he moved with his family to Dej, from where he managed his estate. He built up an intellectual centre in his house, and his guests included the artists István Huber and Sándor Mohy, but also László Mécs, Zsigmond Móricz and even the government commissioner of Northern Transylvania, Count Béla Bethlen. He had a close friendship with Gábor Gaál, editor-in-chief of Korunk, who continued his training as a reserve officer in Dej in 1944, and they worked together on a drama. This relationship had a decisive influence on the later development of Daday’s career.

Following the Second Vienna Decision, under which Hungary regained Northern Transylvania, annexed from Romania by the Treaty of Trianon, the Royal Hungarian Ministry of Religious Affairs and Public Education appointed him first as a school inspector and then as head of the county’s district of public education. He was thus able to offer protection to persecuted Jews and Romanian teachers condemned to be forcibly displaced. For this reason he was placed on the Hungarian gendarmerie’s list of untrustworthy persons.

At the end of World War II, he was briefly elected mayor of Dej. He managed to get the Soviet troops to spare the oil refinery and the town. He worked to establish a genuine democratic system and linguistic and religious equality. From 1945 he was the cultural officer of the Hungarian People’s Association and founder of the Romanian-Hungarian Brotherhood. In his appeal, he formulated the principles of coexistence: ‘Equal rights and equal duties: this is the commandment of the common homeland today. Each one should preserve their national characteristics and racial character, language and culture.’

From the very beginning, he was a contributor to Utunk, edited by Gábor Gaál, where he published his vignettes and short stories under the name Bálint Kovács.

From September 1946 until his death in 1954, he was a teacher and volunteer librarian at the mixed grammar school in Dej, where he taught Hungarian, German, and Latin. Between November 1946 and March 1947 he was imprisoned for five months on false charges. From 21 August to 15 December 1952, he was again remanded in Cluj prison on charges that remain unknown to this day. This was presumably connected with the purge within the Communist Party under the heading of ‘intensification of class struggle’, during which the former Finance Minister László Luka, of Hungarian origin, was sentenced to death on charges of ‘right-wing deviation’.

In 1954, Daday published a collection of short stories, Malomszeg under the pseudonym Bálint Kovács, which was banned due to the offensive reviews it received. This also contributed to the writer’s sudden death.

This persecution also overshadowed the author’s afterlife. In the controversy that followed the publication of Ion Lăncrănjan’s 1982 pamphlet A Word about Transylvania (Cuvânt despre Transilvania), considered a seminal work of anti-Hungarian doctrine, Lăncrănjan identified Loránd Daday as Csaba Dücső, author of propaganda writings inciting war during World War II. His baseless accusation was picked up by the Romanian nationalist press (Dr. László Lakatos investigated: the author of the incriminated writings, Csaba Dücső, is a real person, not the accused Daday). Five years later, in 1998, the Romanian press launched yet another witch-hunt, once again making all manner of false accusations, and in 2000 a member of parliament accused the writer of genocide. The author’s works have still not been translated into Romanian.

*

His writing career

Loránd Daday’s studies published in the 1920s show his strong social sensitivity, for example Christianity and the Social Question (A kereszténység és a társadalmi kérdés), but he was also concerned with the possibilities of artistic representation of reality in Our Art Politics (Művészetpolitikánk – 1921) and the dilemmas of resolving ethnic differences in his Anachronistic Remarks on the Romanian-Hungarian Rapprochement (Korszerűtlen megjegyzések a roman–magyar közeledéshez – 1923). All these topics recur in his later works as well.

The novel Reef (1930), published under his pseudonym Mózes Székely, describes the process by which the representatives of the new power, established after World War I, set out to destroy the spiritual and material well-being of the Hungarians in Transylvania, but also how they extorted the local Romanian peasants and their newly acquired land. The narratological interest of the text lies in the fact that the events are narrated by Wotan, the dog of the captain, who was blinded in World War I, who acts as a medium to convey the events that take place in his presence. This point of view justifies the brevity of the descriptions of the scene, the lack of characterisation, and makes the scenes fragmented and dramatic. The montage technique of the avant-garde also left its mark on the structure of the text.

His play The Map (A térkép), first performed in 1933, presents the fatal outcomes of inhuman manipulation of power (a provocation by the prefect and the secret police) in a concentrated and highly suspenseful way through the depiction of tragic events in the life of a close-knit community, an ethnically mixed family and a Hungarian village.

In his next novel, Thursday (Csütörtök – 1935), also published under the pseudonym Mózes Székely, the perspective is broader: the protagonist is a representative of the Transylvanian Roma. A young man who fights for the great unification – and armed at that – gradually drifts away from the reality of the dream, and eventually becomes the defender of those who have fallen into the minority ranks. Here the editor-in-chief, talking to Albin, says: ‘In this country, Hungarian and Romanian destinies were linked before history itself.’ The final pages of the novel, with their images of the workers’ strike in the Grivica railway workshop being violently suppressed, show the brutality of power becoming universal.

In 1944, he wrote a play entitled Who Owns the Country? (Kié az ország?), which is highly critical of the representatives of the newly established power in Hungary, but also highlights the role of the Orthodox Church in the violent assimilation. The play’s optimistic ending suggests that love and understanding offer the only path to reconciliation. The drama only premiered in 2014.

The main characteristic of the narratives and cartoons that appeared in the pages of Utunk and that were selected for a posthumous volume is the warm humanity of the composition, and the form of the dramatic tension of the scenes.

In 1952, Daday completed the first version of his autobiographical novel, which was published after his death in 1970 in a volume entitled Across the Marsh (A lápon át). The inevitable incorporation of literary politics can be seen by comparing this text with the original version published by Kráter under the title In the Shadow of an Old Manor House (Egy régi udvarház árnyékában). The novelty of this fragmentary story is that the narrator is doubled: one of them is Feri Gál, the militant revolutionary who constantly warns his friend, the author’s alter-ego, the landowner-turned-writer Zalán Péchy, suddenly wealthy in his capacity as heir, of the contradictions of his philanthropic ideals and social situation.

Between 2007 and 2009, Kráter Publishing House published the greater part of Daday’s oeuvre, two plays and a major novel, as well as an autobiographical novel. However, his literary reappraisal has yet to come.

‘My only sin can be the lack of historical perspective to justify me and my writing. Only time will absolve me.’

The biography was written by Zsuzsa Tapodi, translated by Benedek Totth and Austin Wagner.